In my opinion property wrappers are one of the most interesting features of SwiftUI and the upcoming Swift 5.1. Here I’ll share what has caught my attention and what looks the most interesting about this brand new thingy.

The story of the feature.

Nobody argues that Apple is really good at presenting products on stage (devices, tools, language feature). They know how to describe the thing in couple of sentences and expose it in a most compelling way. The description they give usually looks very lightweight which sometimes can confuse even experienced developers.

Right after WWDC’19 some developers (myself including) discussed that finally Apple reacted on such a trendy things like declarative interfaces, reactive paradigm and unidirectional architecture. Only days after some bits and pieces of information emerged and it got clear that the work was ongoing for years before the first release in June’19.

The same happened with property wrappers. The first time the idea about what now is known as Property Wrappers was presented in the end of 2015 as a mail-thread discussion. Proposal #30 in the new shiny swift repository followed soon after. In that proposal the feature was originally called Property Behaviors. At that time Swift was just open sourced, the early adopters were busy migrating their code bases from Swift 1 to Swift 2 and writing JSON parsers and we had to write UIColor.blueColor() and dispatch_queue_create("com.test.myqueue", nil).

At that moment Core Team already realised that new property patterns like lazy or NSCopying kept appearing again and again and maybe it’s not the best solution to keep on adding new modifiers for them into the compiler. That made the compiler logic more and more complex and developers more and more confused. Moreover iOS programmers had to frequently copy-past some getter/setter logic from model to model which also wasn’t good for the code they wrote. That was the main reasoning behind the proposal.

The usage of such a property in case of lazy would have looked as follows:

var [lazy] foo = 1738

But with all the appreciation the proposal was eventually rejected (the rationale). Swift language was too changing and not stable enough at that point so implementing this functionality could cause additional complications. The feature should have being changed together with rapidly evolving language. But the work on the subject haven’t stopped.

The next time the discussion emerged at the Swift forum in March’19 (the pitch). This time the feature was called Property Delegates, the essence and motivation remained the same but its syntax was refined under the inspiration of Delegated Properties in Kotlin.

Our beloved lazy declaration would have looked like:

var foo by Lazy = 1738

Proposal #258 followed that pitch in the end of May’19. The name and the syntax were changed one more time and in the end we got what is a part of Swift 5.1 with usage like:

@Lazy var foo = 1738

I see this small piece of Swift history as a good example of how the features are being added to the language. Sometimes the feature is not ready enough to be added (you can see it in number of other proposals), sometimes it might not make sense at all, or might be rejected by the community. In another case the feature is ready and appreciated but the language is not mature enough, or not in the proper condition to absorb it. Even if eventually they meant to be one whole thing (a new version of the language) there should be “a match” like in a dating app for them to get together.

A brief essence.

Property wrappers are among that things which are easy to describe but not so easy to understand until you use them in practice. Here I’ll not give you any practical examples as there already are lot’s of them around. For instance you may check out this great post on NSHipster or this GitHub repo.

In two words it’s a generalisation of a pattern, another layer of abstraction (what can be better than one more level of abstraction!). I think most of you know the general idea, but let me briefly remind it.

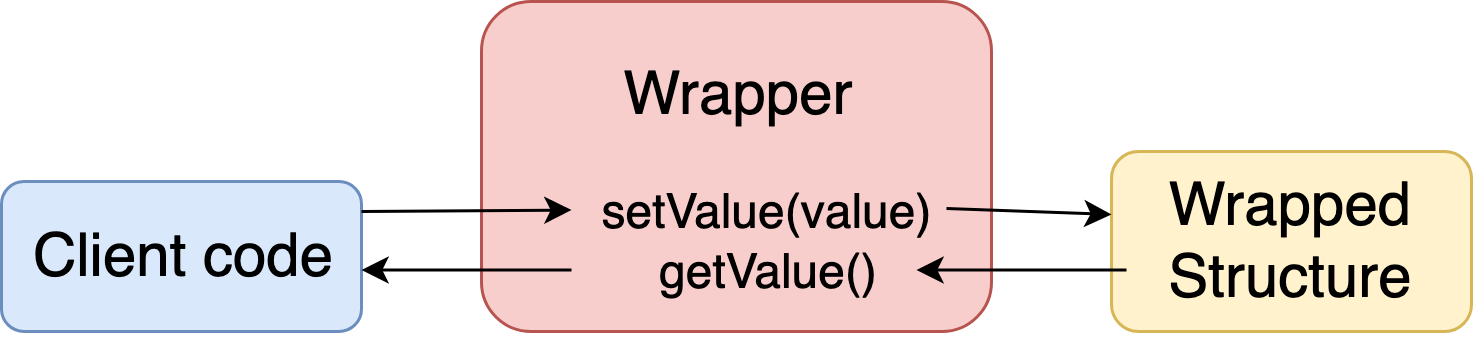

Imagine you have an object’s property and some additional functionality you want to apply when the property’s value is being set of accessed. Something like lazy loading, some data modifications or additional actions. Most of these things are something that you would usually do in property’s accessors (set/get, didSet/didGet, willSet/willGet). Property wrappers abstract these actions from the specific data types and make it applicable to the other data models. You basically take the code to implement it and move it to a separate place which makes possible to reuse it.

Additional functionality.

In a sense property wrappers is an implementation of the decorator pattern, but this “decoration” is restricted to the accessors of this data structure.

Property wrappers can also be treated as a way to add some functionality without changing the object’s original implementation. Consider extensions (categories and extensions to the classes in ObjC, protocol extensions in swift), it is the mechanism to add new methods (and properties - if we don’t mind using some variables in the heap and a bit of runtime magic) to existing data structures. Inside an extension you can refer to the object’s properties and accessible methods.

Property wrapper looks a bit like an extension - it also extend the existing behaviour - but it knows nothing about the object it wraps and its structure (properties, methods). Instead it knows about the lifecycle (when the value is being set or get) so it lets us to do something in between the object and the code using it in the moments of data accessing. Property wrapper is a man-in-the-middle, a proxy object which existence is hidden from the wrapped structure as well as from the client code. Of course we add a modifier like @Modified next to the property declaration but that’s it. No other modifications required for the existing code of both the wrapped object and the client code.

Property wrapper adds new behaviour to a specific instances of the data structure. It doesn’t influence all the other instances of this type (opposite to extension or subclass). So changing the functionality of just one property, one instance of some data structure you shouldn’t worry about any side effects for the other instances.

The layers

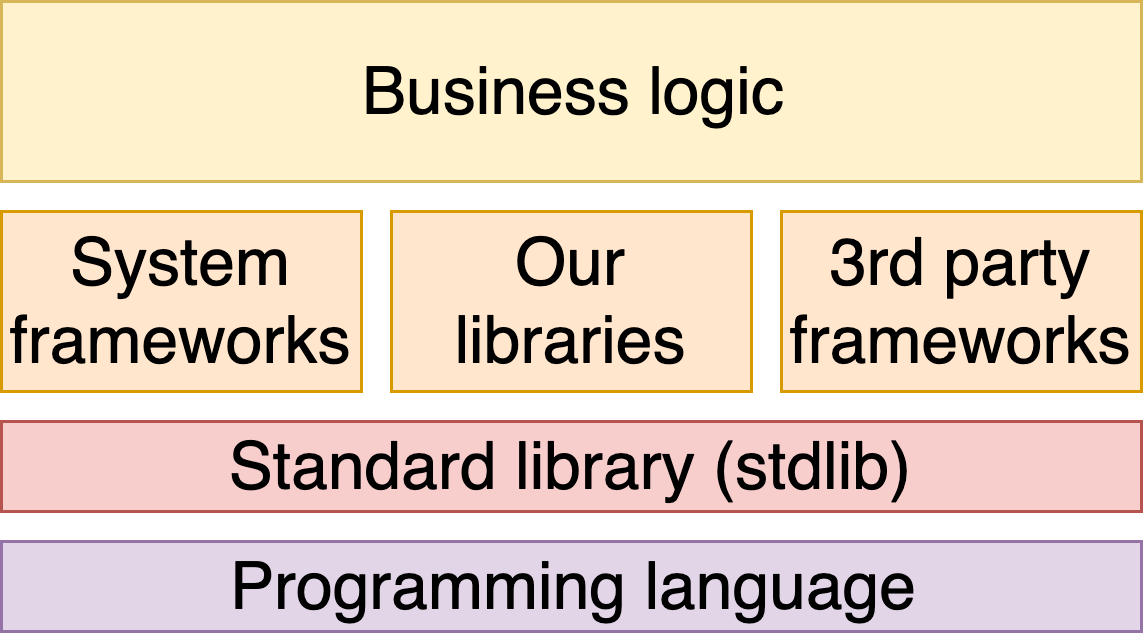

Let’s take a look at our projects considering the levels of code abstraction.

The code we write (let’s call it business Logic) depends on variety of libraries and frameworks. Some of them are system ones, some are our own modules, the others are third party. Libraries and frameworks (as well as our own code) use the language with its syntax and the type system. Somewhere in between the code and the language we can distinguish the standard library (stdlib) which is usually considered as a part of a language by us developers, but the language maintainers see it as something external (Swift Standard Library). We can go deeper into the language and talk about the compiler, its optimisations and translating our code through some intermediate language right into the binary code (I tackled it a bit in one of my previous posts), but it’s out of the scope of this topic.

Each layer has its functionality and features. The language gives us its type system, operators, syntactic constructions and all the other basic things. In case of swift the standard library is the one to add fundamental data types (Int, String), common data structures (Array, Dictionary, Set), some basic global functions and protocols. Then frameworks add some domain specific blocks of functionality which we use in our business logic.

Each layer has its context and area of influence. The language has the widest context and it influences all the code (frameworks, libs, projects, utils) written on this language. So changes on a language level are the most important and the most dangerous. The business logic of a specific application has the narrowest context and influences nothing but one project.

Between the layers there are APIs. The language is kind of API on its own, the stdlib has its API, all the libs and frameworks have their API.

There is a general rule in programming (and in designing the APIs) that you should minimise the context (the visibility) for all the features you add. If you don’t need a constant to be global make it local; if you don’t explicitly need a public function make it private; if you don’t need a class to be subclassed make it final. All this simple heuristics push you to set as minimum context for the functionality as possible. The lesser the context is the easier to control the change, the more predictable is the overall system’s behaviour, the less side effects it brings. It’s also easier to extend the API, to broaden the context than to make it smaller. So the subsystem which operates in the smallest context is more future-proof. Modularity and microservices also come from this rule.

And here come property wrappers. The feature minimises the context of the potential change. If you can add the functionality at the framework/business logic level instead of the language (as it was before with lazy or NSCopying), that’s the way to go.

Simplifying the compiler logic

The more features are integrated into the language itself the bigger is the “set of rules” the compiler uses to translate our code into the binary data. The more job for the compiler the more time it needs to create a binary program. Too much of different language features may also cause clashes on the compilation stage and errors with vague description. So there should always be some balance for the language and its compiler between being useful/helpful and being cumbersome/misleading.

As the original proposal says, property wrappers meant to simplify the compiler logic (among other reasons). Better said they should prevent the over-complication of it in future. It doesn’t seem like they remove lazy from the language as it can be easily implemented now with property wrappers. But swift maintainers gave the developers the tool to implement something similar without adding new features to the language, without adding new rules to the compiler, without making the compiler slower and more complex. So instead of filling in proposals and chasing the maintainers for adding a new feature, now in some cases you can just add this functionality on a level you have access yourself.

Syntax and aesthetics

Before swift 5.1 if you see @ in swift code you know that you deal with some language feature. Getting back to the layers, @ meant something belonging to the language or stdlib layer. Although the amount of such modifiers has been growing quite fast, we still could remember the majority of such keywords. Property wrappers now let us to introduce our own @-prefixed constructions. Hence we are losing this clear border between the language features and our third party code. When moving the burden from the compiler to our code we blur the edge between these worlds. Making the language and the compiler simpler we make the overall code base more complex.

So now in code you may see something like this:

class Dessert {

@DecoratedWithChocolate @Diced @Sliced var banana: Banana

}

Functional? Flexible? Fancy? Yep. Readable?… I’m not sure. That’s subjective. I think at some point we all will get used to it. Until then I share the concern that all these additional @s make the code less structural and a bit more messy. The edges between the API layers become blurred. This steeper learning curve is the price we have to pay for the ability to use this construction.

The readability suffers especially considering the parameters you can add to the wrapper:

@UserDefault("test", defaultValue: "Hello, World!", userDefaults: userDefaults)

var test: String

The chicken or the egg?

There are some thoughts around about how much SwiftUI dictated the evolution of swift. Several features were rushed to be included into the language before Swift 5 release. Some of them were still not release on time (mostly because swift evolution process is not completely controlled by Apple), so when SwiftUI was presented they have not yet been parts of the language. So they were planned for Swift 5.1 and SwiftUI had to use them internally other then the built-in language features. These features being a general improvements to the language eventually empowered SwiftUI and the whole picture appeared from the separate pieces.

The question what came first: property wrappers or SwiftUI may seem a bit naive. We see that there is quite a story behind this language feature and the (official) original motivation have nothing to do with SwiftUI. Moreover the discussion was started long before SwiftUI… But was it? There are also signs, evidences and replies from the members of the Swift Core Team that SwiftUI was under development years before the release at WWDC’19. Some even say the first research was started before Swift was released in 2014. So who knows whether or not we would have had property wrappers in the language if not SwiftUI.