In this post I’ll try to systemise the knowledge about major formats and types of data serialization in iOS development. I will also compare ObjC approach to the problem (NSCoding) with the one we got in Swift 4 (Codable) and will take a look at some specific use cases like interop between them and the ability to work with complex object graphs.

Contents:

- Serialization as a separate process

- NSCoding

- NSCoder and NSKeyedArchiver

- JSON

- Plist

- Other formats

- Codable

- Some benchmarks and comparison

- NSKeyedArchiver encoding Codable

- Encoding complex object graph

- Codable as a replacement for NSCoding

Serialization as a separate process

Serialization is the process of translating data structures or object state into a format that can be stored or transmitted and reconstructed later (possibly in a different computer environment).

[“Deserialization”; is an opposite process when you recreate your models from the serialised data. For simplicity in most cases I’ll be talking only about serialization.]

Quite often serialization is only considered as a part of archiving data on disc. For a long time we would naturally use this code to store NSArray or NSDictionary to file:

NSURL *localURL = …

NSDictionary *someDict = …

[someDict writeToURL:localURL atomically:YES];

You can use this ObjC API in Swift as well:

let hosts: [String] = ["host1", "host2"]

try? (hosts as NSArray).write(to: fileUrl)

Here you serialise an object and store it to a file with just one line of code. Simple and handy. But there are some obvious limitations and downsides of this approach: you cannot use it for your custom classes, it doesn’t look nice in Swift with the type cast (even if you properly handle the errors). But more importantly, serialization here inextricably coupled with persisting the data.

Do you see serialization in the code snippet above? Me neither, but it’s implicitly inside.

Using this API you don’t control the process and you cannot adjust it. Until you take a look into the file you wrote on disc you have no idea the object was serialised into XML.

The most popular applications for serialization are local storing and sending the data over the internet. But there are some other cases: for instance, passing the data to a third party library or transferring it to an external device via bluetooth. The idea is that there are two (or even more) incapsulated systems separated from each other. (In case of saving/retrieving the data locally we can consider the same system in different points in time as two separate systems). One system is a transmitter, another one is a receiver. There also is a protocol, an agreed data format expected on the receiver side. Serialization is the way to convert the objects the first system uses in its operation activity into this agreed format. And then it doesn’t matter how this data supposed to be used: stored or passed somewhere; it’s another separate processes.

Let’s take a look at the most popular formats and different ways of handling serialization in iOS development.

NSCoding

NSCoding is lightweight ObjC protocol with two methods: -initWithCoder: and encodeWithCoder: which has been around since iOS 2. Your custom classes implement it to be ready for serialization/deserialization. Inside the implementation of this methods you specify how different properties of your object (the values inside these properties) are being encoded into some kind of key-value container. You describe how your object supposed to be transferred into key-value pairs.Eventually some coder will serialise this container to binary data.

The implementation of the encoding method usually looks pretty much the same:

func encodeWithCoder(coder: NSCoder) {

coder.encodeObject(self.name, forKey: "name")

coder.encodeInt(Int32(self.age), forKey: "age")

// and so on

}

Sometimes you might need more sophisticated way of encoding some properties, and here you have flexibility to implement pretty much whatever conversion you want. Also this way you can easily handle different versions of your custom class (with some added, changed or removed properties). But other than that it’s a lot of boilerplate code which you have to write for every data model. The bigger the model is the more code you have to write.

If you use conformance to NSCoding in Swift your models has to be classes (inherit NSObject… or manually implement all the NSObjectProtocol methods), which makes it impossible to use for Swift structs and enums.

Another flaw of this protocol from Swift’s perspective is its type dynamism. You basically use key-value coding when passing the values to the coder, so every value can be passed to every key. Eventually when you need to decode these values back you cannot be sure in their types, which is how ObjC works, but it costs you extra type-validation when working with this code in Swift.

NSCoder and NSKeyedArchiver

NSCoder is an abstract class that serves as the basis for objects that enable archiving and distribution of other objects. NSCoder operates on objects, scalars, C arrays, structures, and strings, and on pointers to these types.

So you will not be surprised that it has tons of methods for encoding and decoding all this types like:

func encode(Int, forKey: String)

func encode(CMTimeRange, forKey: String)

func decodeCGPoint(forKey: String) -> CGPoint

func decodeUIOffset(forKey: String) -> UIOffset

Nowadays in Foundation there is only one concrete subclass of NSCoder and that is NSKeyedArchiver (there also were NSArchiver and NSPortCoder, but they have never be available in iOS development and are deprecated now).

NSKeyedArchiver is an archiver class supposed to work with objects adopted NSCoding protocol. To serialise such object into binary data you just call

let data = try? NSKeyedArchiver.archivedData(

withRootObject: yourObject,

requiringSecureCoding: false

)

NSCoding implementation of the object tells the coder how to pack object data into key-value container, and NSKeyedArchiver handles turning this container into binary data.

NSKeyedArchiver can be also used to serialise and automatically write output data to file (the same way as methods we started this post from):

NSKeyedArchiver.archiveRootObject(yourObject, toFile: fileUrl.path)

NSKeyedArchiver can encode data into two formats: binary (the default one) and xml. The former is much more compact, the latter is human readable and editable but takes more disc space. If you want to change the format to xml you can do it this way:

let archiver = NSKeyedArchiver(requiringSecureCoding: false)

archiver.outputFormat = .xml

archiver.encodeRootObject(yourObject)

let data = archiver.encodedData

You might have already noticed `requiringSecureCoding` parameter we use for NSKeyedArchiver. If we pass `true` there we assume our coder to work only with objects which adopt NSSecureCoding protocol. NSSecureCoding inherits NSCoding but also guarantees that resulting archive contains the classes it claims.

To adopt NSSecureCoding you have to add this property to your models:

static var supportsSecureCoding: Bool {

return true

}

If you use NSSecureCoding you have to explicitly use Foundation classes like NSString instead of String and wrap your primitives into reference types:

aCoder.encode(self.name as NSString, forKey: "name")

aCoder.encode(NSNumber(value: self.age), forKey: "age")

JSON

The most popular format nowadays is JSON. Up to iOS 5/macOS 10.7 Foundation didn’t have a built-in functionality to parse JSON, so there were several different third party libs for that (check out the list here). Finally NSJSONSerialization class appeared and took it over.

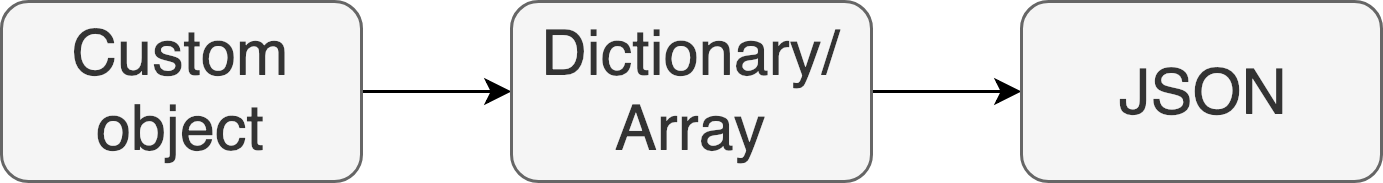

In iOS serialization chain for encoding your custom objects to JSON data looks like this:

NSJSONSerialization offers only the second part - serialization from NSDictionaty/NSArray to JSON, so you still need to do the mapping from your custom object to NSDictionary. The class is straightforward and supposed to be used like this:

NSDictionary *objectDict = @{

@"name" : @"John Smith",

@"age" : @(34),

@"gender" : @"male"

};

NSError *error;

NSData *jsonData = [NSJSONSerialization dataWithJSONObject:objectDict

options:kNilOptions

error:&error];

As I mentioned the root object of the tree we aim to encode can be NSDictionaty or NSArray only. But there are some other limitation for using NSJSONSerialization:

- all objects are instances of NSString, NSNumber, NSArray, NSDictionary, or NSNull.

- all dictionary keys are instances of NSString.

- Numbers are not NaN or infinity.

There are some options you can pass to NSJSONSerialization for encoding and decoding data:

1. Encoding (NSJSONWritingOptions):

- PrettyPrinted - using white space and indentation to make the output more readable (adding some extra bytes to resulting data)

- SortedKeys - sorting keys in lexicographic order

2. Decoding (NSJSONReadingOptions):

- MutableContainers - arrays and dictionaries are created as mutable objects

- MutableLeaves - strings are created as instances of NSMutableString.

- AllowFragments - tells the parser to allow top-level objects that are not an instance of NSArray or NSDictionary.

If you don’t want to specify any options you can pass kNilOptions-constant in ObjC code or an empty array in Swift.

Back to our serialization chain: with NSJSONSerialization we still need to map our custom objects into arrays and dictionaries. For that purpose you would sometimes use manual key-value mapping inside your model object:

- (NSDictionary *)jsonDict {

return @{

@"name" : self.name,

@"age" : @(self.age),

@"gender" : self.gender

};

}

But it’s also possible to automate it using class inspection in ObjC runtime.

#import <objc/runtime.h>

...

unsigned int outCount, i;

objc_property_t *properties = class_copyPropertyList([self class], &outCount);

for(i = 0; i < outCount; i++) {

objc_property_t property = properties[i];

fprintf(stdout, "%s %s\n", property_getName(property), property_getAttributes(property));

}

free(properties);

Here we get a list of all the properties of a given class with some attributes including the property type. So we can generalise the algorithm to serialise every object into JSON data. Optionally we can use some mapping tables and transformations if exact keys or values of the object properties are not what we want to see in JSON. There are a number of libraries out there successfully using this approach (I had a pleasant experience using JSONModel).

Plist

Plist (from “property list”;) is a structured way to represent and persist a single object or an object tree. The format has appeared in NeXTSTEP operation system and made its way through decades to contemporary macOS/iOS ecosystem.

Generally plist serialization in Foundation world looks like JSON serialization. We have NSPropertyListSerialization (PropertyListSerialization when calling from Swift) which is being around since macOS 10.2/iOS 2. The class - an older brother of NSJSONSerialization - makes conversion between plist (which is represented in memory by instance of NSDictionary or NSArray) and binary data (represented by NSData).

NSError *error;

NSPropertyListFormat format;

id plist = [NSPropertyListSerialization propertyListWithData:data

options:NSPropertyListImmutable

format:&format

error:&error];

NSPropertyListSerialization works only with limited amount of Foundation classes: NSData, NSString, NSArray, NSDictionary, NSDate, and NSNumber. If an instance of some other class is inside the dictionary or array you want to encode serialization will fail.

Property list can be encoded/decoded in two formats: xml (NSPropertyListXMLFormat_v1_0) or binary data (NSPropertyListBinaryFormat_v1_0) with their pros and cons (pretty much the same as for NSKeyedArchiever). There is one more format - OpenStep (NSPropertyListOpenStepFormat) which is deprecated now and available only for reading.

(Here you can find some details about the structure of plist binary format)

There is an options parameter in both serialising and deserialising calls. It has to do with mutability. When you deserialise an object from plist data you can tell serialiser if you wan to have mutable containers - NSPropertyListMutableContainers value. If you pass NSPropertyListMutableContainersAndLeaves serialiser will try to make all the values mutable if the value class has its mutable counterpart.

When serialising objects to binary data you cannot save mutability info of your objects, so options parameter makes no sense and you would always pass an empty value.

Codable

All these APIs for serialization were good enough for ObjC but had some significant limitations for Swift. I’ve already mentioned that NSCoding cannot work with swift native structs and enums (although developers came up with some workarounds), and if you want to use it in swift classes you have to make them visible in ObjC. Also all the serialization APIs are needed to be adjusted for Swift’s strong type safety. So creating some tools for serialisation in a standard library was the matter of time.

Codable (which unites Encodable and Decodable protocols) was implemented in Swift 4 and made developers’ lives much easier.

As till Swift 4 there were no built-in native solution for data serialization, plenty of third party libraries appeared to fill this gap in. In swift-evolution proposal for Codable the authors reason that out of these solutions (for JSON parsing specifically) there is none which is both easy to use/implement and type safe enough.

It’s not explicitly said in the proposal but obviously the ability to generate Codable implementation by compiler, moving this workload from a developer, is a significant benefit of the approach we eventually have seen implemented.

Each protocol (Encodable/Decodable) consist of just one required method. The great news is that if all the object’s properties conform to Codable themselves the compiler will be able to generate the implementation for the object. If the condition isn’t met or you need some additional customisation you can write the methods manually. For Encodable it will look like this:

func encode(to encoder: Encoder) throws {

var container = encoder.container(keyedBy: CodingKeys.self)

try container.encode(someObjectProperty, forKey: CodingKeys.someKey)

// handling all the object's properties

}

Basically that’s the same code as the one generate by the compiler for you.

By making your object conform to this protocols you get an ability to decode them to both JSON and plist format out of the box - just pick a corresponding encoder.

Encoder is an object which does the actual serialization for the model object. There are two built-in encoders: JSONEncoder and PropertyListEncoder for corresponding formats. All the system is protocol based and there are specific Encoder/Decoder protocols so it’s possible to implement your own coders for another formats which can work with all Codable models (an example from Mike Ash).

The usage of built-in encoders (as well as decoders) is trivial (as far as your yourCustomObject conforms to Codable):

let jsonData = try JSONEncoder().encode(yourCustomObject)

This way we have ent-to-end serialization from your custom object right into the binary data.

If you take a look inside Swift source code you will see that JSONEncoder uses the same NSJSONSerialization from Foundation (which is called JSONSerialization when being used from swift) that I’ve mentioned before. JSONEncoder uses Encodable implementation of a model object as an instruction how to wrap all its properties into NSObjects. Then it puts them to a container (which is actually an array of NSObjects) and passes the container to JSONSerialization for the conversion into binary data. So basically JSONEncoder utilise Encodable implementation to map your custom objects into a data structure which can be used by good old NSJSONSerialization. So Swift safely and elegantly does the same that we developers had been doing before: performs some kind of mapping for custom model’s properties into a Foundation-based container and then uses NSJSONSerialization.

The same is fair for PropertyListEncoder as well.

(If you want to read in details about complex use cases for Codable/Encodable/Decodable and all the capabilities of JSONEncoder I refer you to this or this posts)

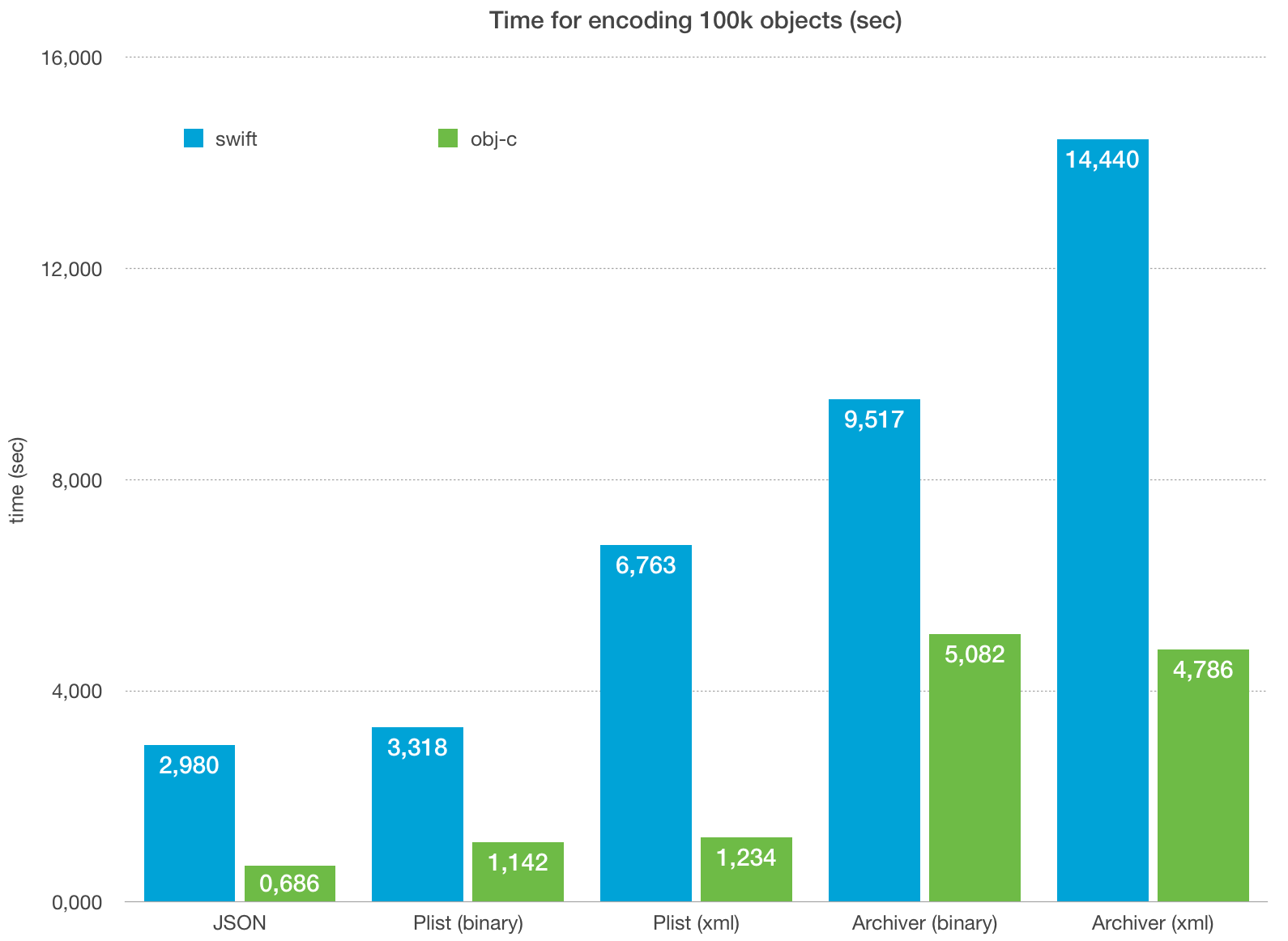

Some benchmarks and comparison

It’s hard to fairly compare all the different approaches regarding their speed or resulting data size because originally they serve completely different needs.

NSKeyedArchiver (as well as NSArchiever before) suppose to deal with complex object graphs. It takes into consideration such things like multiple references to the same object, object replacement, calling each object’s encodeWithCoder() method, object graphs, and so on. If you use binary output it also takes some extra effort to make the output smaller than it would otherwise be. So no surprise it takes a lot of time for NSKeyedArchiver to serialise a custom object or object graph.

JSON/Plist serialisers originally would work only with dictionary or array and some small set of predefined Foundation types. It makes the life of an encoder much easier so it can spend less time and be more efficient in disc space.

Talking about the size of output data, JSON is the most compact format out of these three and plist is a bit more verbose one (2-4 times difference). The output of NSKeyedArchiever with all the metadata it provides can take up to 10 times more disc space than JSON. But usual eventual use case for NSKeyedArchiever’s serialization is data persistence, so here the proper data structure is more important than the occupied space.

When talking about ObjC the comparison may only be done for NSDictionary or NSArray (JSON/Plist serialisers don’t work with custom types) and the results are more or less predictable: JSON is the most compact format, JSON and plist are both quite speed efficient and NSKeyedArchiver sucks (you can find one of the benchmarks here)

But in Swift we are able to use all these 3 encoders for our custom classes conforming Codable so the conditions are equal for all of them.

I did a trivial benchmark myself to check how the things really are. After I took a look at the results for Swift I decided to include Obj encoding as well for custom objects. All the tests are done for small objects.

Here are the results:

Serialization in Swift.

- NSKeyedArchiver is the slowest one - let’s remember that the ability to handle Codable was added just for compatibility to this ObjC API. JSONEncoder/PropertyListEncoder which are native for Codable do the job faster.

- Plist serialization is slower than JSON serialization. But for binary plist format the difference is almost negligible. Binary plist is considered as “not human readable”;, but basically it’s just the matter of application you use to open the file. JSON is also not readable until you open it in a text editor 😉

- Serialization into binary format takes more time than XML for both plist serialiser and keyed archiver. Don’t forget that the archiver puts more metadata to the output XML, so its output file is much bigger.

Serialization in ObjC:

- Here we don’t compare NSKeyedArchiver with JSON/Plist serialisers for custom objects. For serialisers I used manual mapping (object property -> dictionary key) which is way faster than general archiver’s approach with key-value container. So for JSON/Plist we still serialise dictionary instead of the object.

- Comparing JSON with plist serialization we see that the former is twice faster than the latter.

- We can see that there is no significant difference between binary and XML formats for both plist serialiser and keyed archiver.

Comparing Swift and ObjC:

- I put JSON/Plist serialization for ObjC and Swift next to each other to show how big is encoding work of Codable implementation (the difference between the ObjC and Swift bars for each type) and how fast is actual work of ObjC serialisers (which is common for both languages)

- Check out NSKeyedArchiver: It’s not surprising that Swift is slower here as well, keyed archiver is completely an ObjC API.

NSKeyedArchiver working with Codable

After Codable was introduces the necessity to use NSKeyedArchiver from Swift almost disappeared. Now to store some custom object on disk with an equal effort you can use JSONEncoder or PropertyListEncoder for serialization. NSKeyedArchiver is not the main coder for serialising custom objects anymore. But if you want to use it with models conforming to Codable you can do it (without implementing NSCoding protocol methods). Swift team specifically introduced two new methods for NSKeyedArchiver to make it work with Codable:

// These are provided in the Swift overlay, and included in swift-corelibs-foundation.

extension NSKeyedArchiver {

public func encodeCodable(_ codable: Encodable?, forKey key: String) { ... }

}

extension NSKeyedUnarchiver {

public func decodeCodable<T : Decodable>(_ type: T.Type, forKey key: String) -> T? { ... }

}

For encoding the root object you would use an encoding method like this:

do {

let archiver = NSKeyedArchiver(requiringSecureCoding: false)

archiver.outputFormat = .binary

try archiver.encodeEncodable(yourObject, forKey: NSKeyedArchiveRootObjectKey)

archiver.finishEncoding()

// then you can use encoded data

try archiver.encodedData.write(to: fileUrl)

} catch {

print("Couldn't write file: \(error)")

}

Another case is when you want to encode the root object with let’s say JSONEncoder. This object almost conforms to Codable, but it has just one property of a legacy ObjC class which cannot adopt Codable. So your option is to manually implement Codable’s encode() method where you use NSKeyedArchiver for converting this legacy property to binary data:

struct Person: Codable {

let name: String

let workHistory: WorkHistory // cannot be extended to adopt Codable, but conforms to NSCoding

enum CodingKeys: String, CodingKey {

case name

case workHistory

}

func encode(to encoder: Encoder) throws {

var container = encoder.container(keyedBy: CodingKeys.self)

try container.encode(name, forKey: .name)

let workHistoryData = try NSKeyedArchiver.archivedData(withRootObject: workHistory, requiringSecureCoding: false)

try container.encode(workHistoryData, forKey: .workHistory)

}

init(from decoder: Decoder) throws {

let container = try decoder.container(keyedBy: CodingKeys.self)

name = try container.decode(String.self, forKey: .name)

let workHistoryData = try container.decode(Data.self, forKey: .workHistory)

workHistory = try NSKeyedUnarchiver.unarchiveTopLevelObjectWithData(workHistoryData) as! WorkHistory

}

}

Other formats

Of course JSON and Plist are not the only formats available out there. So there are some other serialization approach specified for different needs

For platform-agnostic data exchange over the network there are some alternatives like Protobuf or MessagePack which claimed to be better in various different metrics (protobuf even has an official Swift library).

For local data persistence there is FastCoding.

There also are some other popular protocols which are not ported to Cocoa platforms yet like Apache Thrift from Facebook or FlatBuffers from Google.

Personally I didn’t have a chance to use any of them in production so I just mention them as possible alternatives. You can find a lot of information about the formats, libraries to handle them and use cases where it makes sense to look into these alternatives.

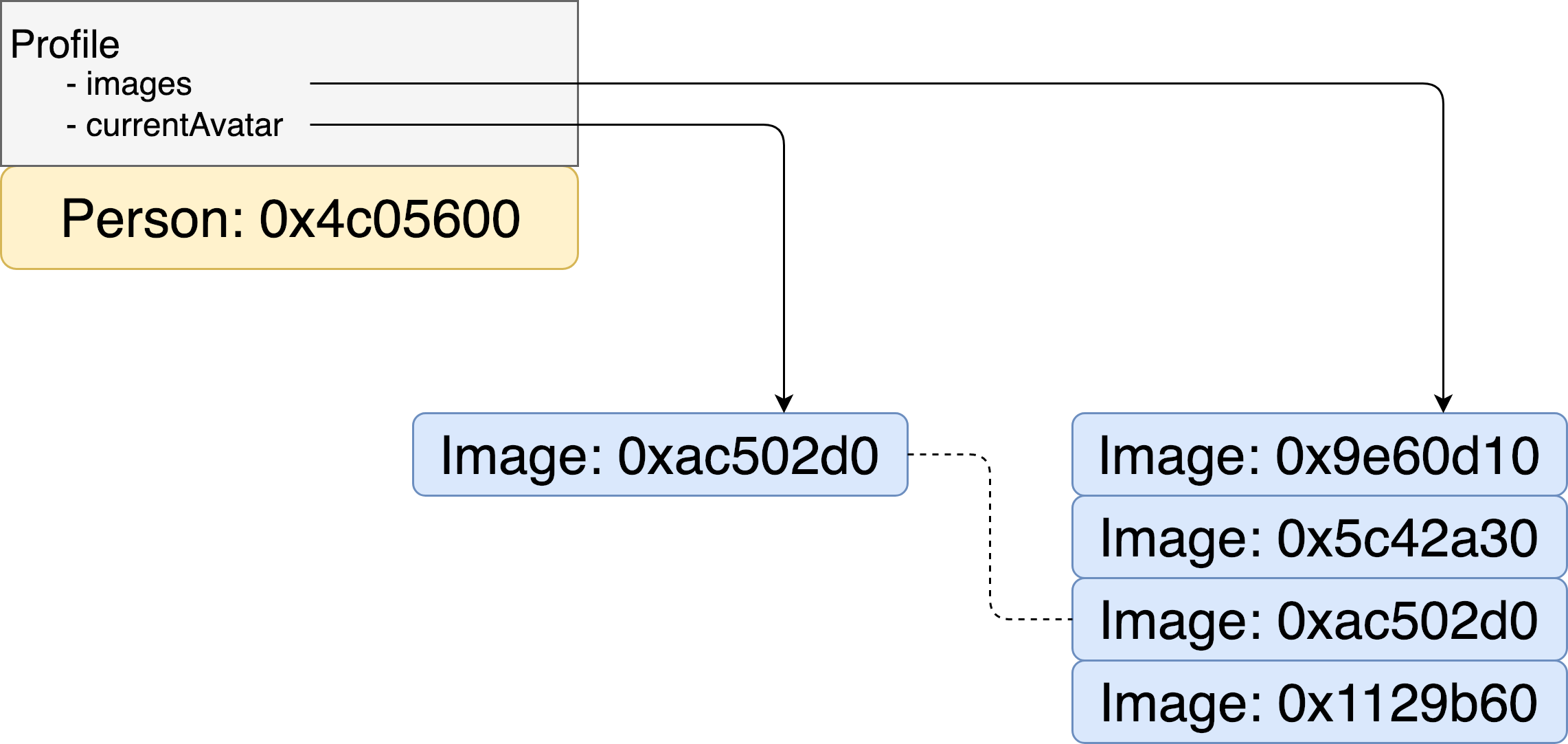

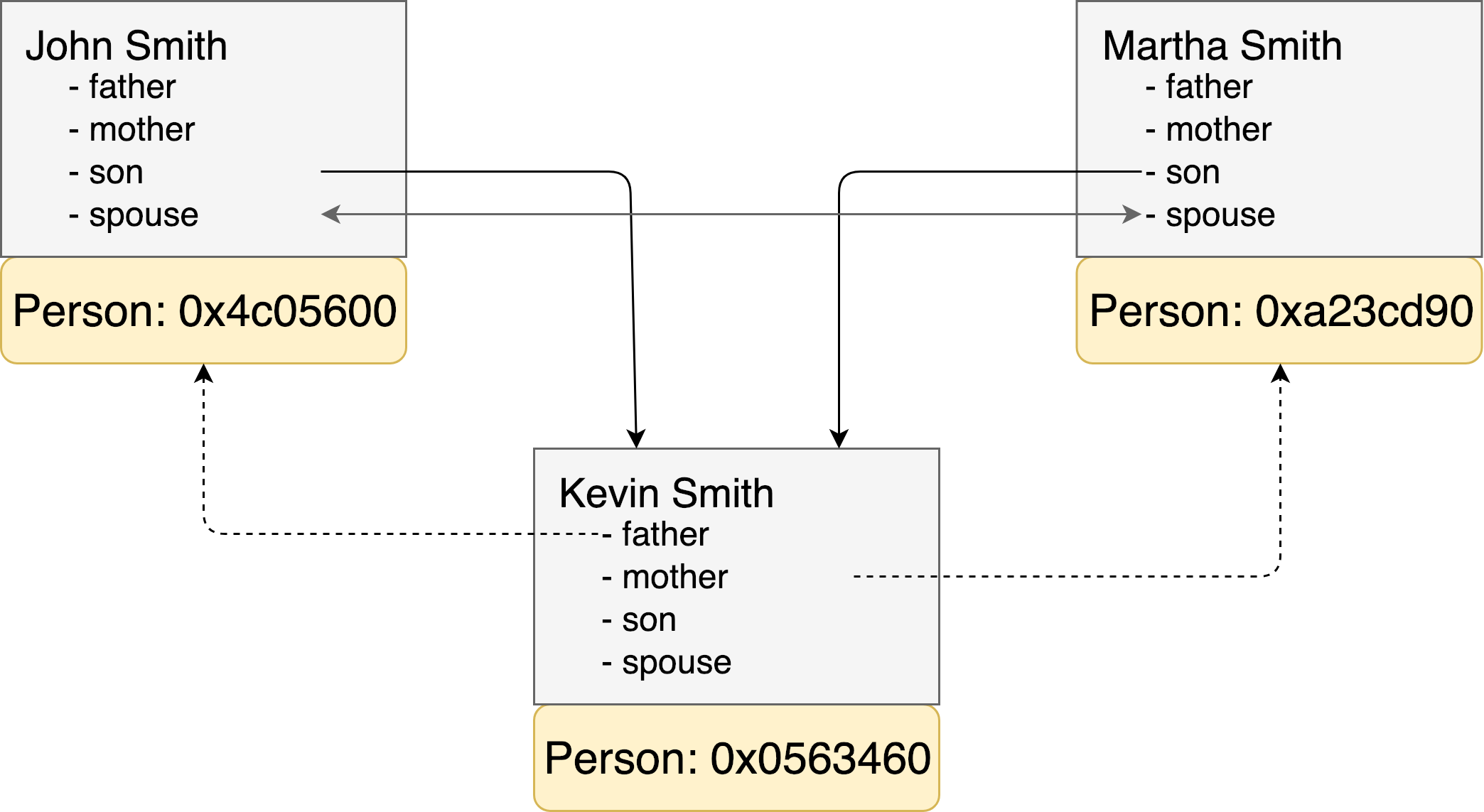

Encoding complex object graph

Quite frequent use case for serialization is persistence of complex object graphs on disk. (For example inthisNSHipster’s post Mattt considers NSCoding/NSKeyedArchiver as a valid alternative to Core Data.)

All the mentioned encoders easily handle not only simple objects, but also quite a complex object trees with lots of nested items. But if you want to encode a complex graph it’s another task with several additional complications.

Talking about “complex graphs”; I mean a structure which has at least one of these conditions:

-

Several references to one object

-

Cyclic references between objects

If the graph has several references to the same object inside itself the problem is to consider uniqueness of the object. The encoder has to have some table of occurred object for not to encode the same object several times. If an object is passed to the encoder more than once it should encode only a reference. Eventually when the archive is decoded back and the graph is rebuild there should be references to the same instance, but not several different objects.

If the graph has objects referencing each other, it’s tricky for the encoder. If it doesn’t consider this possible cycles and blindly follows every link of every object it would go to an infinite loop.

Another complication for complex structures is that it might be not always appropriate to archive the entire graph. A good example is a view hierarchy. A view has many links to other objects: models, subviews, superviews, formatters, targets, gesture recognisers, and so on. If the view encoded all of its references to these objects, the entire application would get pulled in. Some objects are more important than others, though. A view’s subviews always should be archived, but not necessarily its superview. In this case, the superview is considered an extraneous part of the graph; a view can exist without its superview, but not its subviews. A view, however, needs to keep a reference to its superview, if the superview is also being encoded in the archive.

All this problems are considered in NSCoder’s API and its concrete implementation - NSKeyedArchiver. Uniqueness of the objects is controlled within the context of one graph encoding which is opened by calling `encodeRootObject:`. Multiple and circular references are also being properly managed: no infinite loops and only one instance of each object.

NSKeyedArchiver has a set of other useful things like default values for missing keys, type coercions or an ability to substitute objects. You can read more of that here (https://developer.apple.com/library/archive/documentation/Cocoa/Conceptual/Archiving/Articles/archives.html)

Unfortunately most of that NSKeyedArchiver’s benefits work only for objects adopting NSCoding protocol. Neither reference control nor cyclic dependencies resolving doesn’t work for Codable.

Moreover Codable models behave the same with JSONEncoder and PropertyListEncoder, having the same issues if talking about complex graphs. So currently for Codable there is no built-in solution for this problem.

Swift team assured that this functionality was in the plan for Codable from the beginning, but they didn’t have time to accomplish it in time for Swift 4 release. The main difficulty has to do with Swift initialisation process which is much stricter that ObjC’s one. It’s still an ongoing discussion and work in progress and hopefully we will see some solution in the standard library soon.

Until then you have several options for encoding/decoding complex graph structures in Swift:

- Use NSKeyedArchiver + NSCoding. Good old ObjC APIs work smoothly from Swift.

- Implement an additional compatibility layer between the calling code and the actual encoders. Create a `reference table` for checking an identity of the encoding objects.

- Implement your own encoder/decoder pair. It’s the most time consuming option, but this way eventually you can use synthesised implementation for actual encoding/decoding in your models.

- You can use some third party solutions. The problem is common enough so there are already some attempts to implement a solution. (https://github.com/BigZaphod/Archivable, https://github.com/cherrywoods/swift-meta-serialization)

There are couple of very informative discussion on the matter in swift forum here and here.

Codable as a replacement for NSCoding

(as a conclusion)

Obviously Codable is the future for serialization in iOS/macOS platforms. So can we consider NSCoding as a legacy API and forget about it when considering Swift?

Codable (with Coder protocol) came from NSCoding (with NSCoder abstract class) and inherited its general mechanics. We pass an encoder into encode() method of the model and the model translates itself into a number of key-value pairs which it passes to the encoder. But Codable is different in amount of use cases it covers.

In the beginning we pointed out that even before Codable we should have distinguished serialization from archiving, but the only way we utilise NSCoding is data persistence. NSKeyedArchiever which is used together with NSCoding serialises data in a format which makes it almost impossible to deserialise the data in another ecosystem (without NSKeyedUnarchiver and the same data model as was used for encoding). NSCoding has nothing to do with JSON or plist encoding/decoding. So the only practical approach is to persist data between app launches.

Codable introduces a completely different approach. Codable implementation may be used for serialising objects not only to JSON or plist, but to some custom formats as well. It decouples serialization from archiving and makes it more independent. In this regard multipurpose Codable has more value than NSCoding.

NSCoding has its own benefits. lets mention them one more time.

You can use NSCoding in both languages. In mixed ObjC/Swift projects when legacy models are written in ObjC it doesn’t matter if you write all the new code in Swift - you still cannot build general encoding mechanism (working for both languages) based on Codable.

The second point is wide adoption of NSCoding in Apple frameworks. All of the Foundation value objects and most of the Application Kit and UIKit user interface objects adopt NSCoding. The list of classes adopting Codable now is not so big. So it might cost you quite an effort to write extensions for classes you want to serialise/archive (for instance if you want to persist your app’s view hierarchy).

For serialising complex object graphs you cannot use pure Swift and Codable without an additional harness. But you can easily do it with NSCoding.

Saying that I don’t think that Codable can completely replace NSCoding in our code, at least now. You can leverage its benefits for some use cases like JSON encoding or serialization of simple structures to store them on disk. But there are still set of use cases when NSCoding is a better approach. Our job is to know the peculiarities and restrictions of both this approaches and use them in appropriate situations.

(One more interesting case on the topic can be found in this post: Serialization of enum with associated type)