This post is basically a continuation of the topic started in the previous ones.

In Protocol Extensions we’ve mentioned all the different use cases for this language feature. Now let’s consider some hidden complications which we get together with all the power.

First of all, most of the drawbacks of general swift extensions are fair here as well. (I discussed them in Dark side of extensions in Swift).

But there are also some additional ones.

Protocol extensions bring extra complexity

One of the main drawbacks of the extensions, in general, is the implicitness of added functionality. When you look into the object’s implementation you have no idea about it’s extended functionality. The extension may reside in a separate file far away in the project tree. So if you are not too familiar with the code you are likely to be unaware about it.

In the case of protocol extensions, the situation might be even more complicated. We have a protocol, we have its extension and we have a data type which conforms to this protocol (maybe this conformance also implemented via a data-type extension).

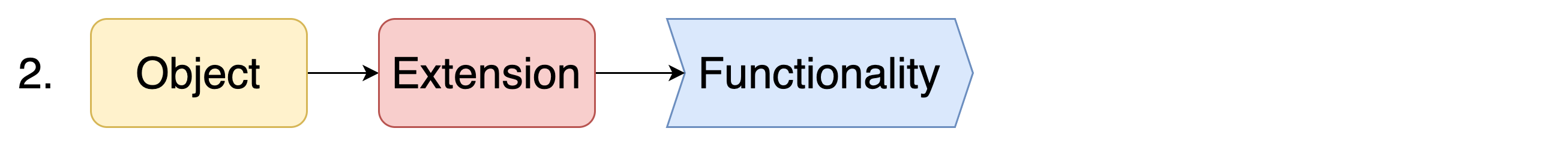

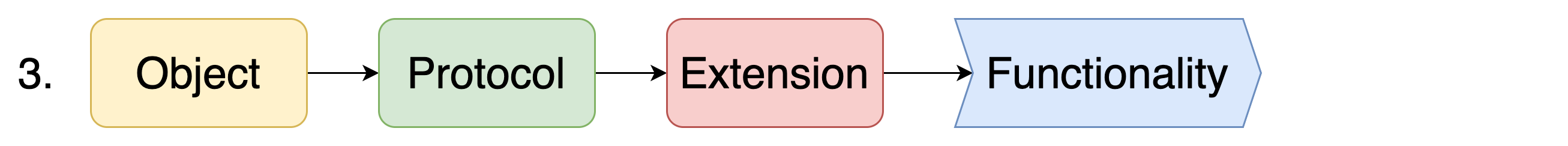

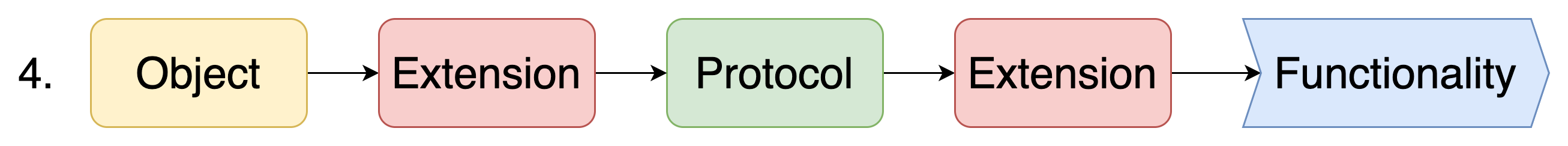

Compare the following 4 cases. The same function call on a structure can be backed up by different chains of object relations:

let collection = MyCollection()

collection.filter()

struct MyCollection {

func filter() {

// functionality

}

}

struct MyCollection { ... }

extension MyCollection {

func filter() {

// functionality

}

}

struct MyCollection: Filtrable { ... }

protocol Filtrable { ... }

extension Filtrable {

func filter() {

// functionality

}

}

struct MyCollection { ... }

extension MyCollection: Filtrable {}

protocol Filtrable { ... }

extension Filtrable {

func filter() {

// functionality

}

}

When you investigate or debug such code, you usually manipulate such chains of connections from the object to its function. And at every moment you have to keep many of them in your head. And we all know that the context we are able to keep in mind is limited. So every extra connection, as well as every level of abstraction, makes it more difficult to mentally juggle entities when we reason about the code.

A protocol extension also brings us some extra actions in the IDE when we investigate this Object - Functionality relations.

Let’s imagine you want to gather information about the object’s functionality. Other than the basic implementation it might conform to a number of protocols. Possibly, you have no idea if they are just interfaces or these protocols also have extensions. So you check them one by one, finding out which have extensions and what it inside these extensions. Only after that finally, you get the full picture of the object’s behaviour.

The other way around: you want to jump to a function definition. You click to a method call in the code (collection.filter()) and it leads you to some protocol extension. If you know Xcode well enough, you cannot be sure that there is a connection between the object you are interested in and the functionality in this extension. Sometimes our IDE gets confused and redirects us to some other function with the same signature. So you need to get back to the object and find if it conforms to that extended protocol.

More use cases for protocols.

In Several faces of protocols we mentioned different use cases which shape different flavours of protocols. Extensions add a couple more: default method implementation, additional functionality.

That’s great how many use cases protocols have in Swift. But as a result, when you see a protocol in code, you cannot say for sure WHAT exactly are you looking at. Is it an interface or a compile-time constraint? Does it have an extension somewhere in the project? What is there in the extension: some default implementations (which ones?) or maybe even some additional functionality?

Honestly, even generics seem to be a more straight forward language concept in Swift than protocols.

Static nature of additional functionality.

In Protocol Extensions we described a difference between default implementation and additional functionality. Now let’s focus on the static nature of the latter one.

Imagine the following situation:

// we have a var of a type `NewsProvider`

var newsProvider: NewsProvider

// at some point we assign it an instance of a specific type

newsProvider = RussiaTodayNewsProvider()

// at some point we do the filtering

let filteredNews = newsProvider.applyFilter(filter: filter)

// NewsProvider.applyFilter() implementation is used

Even if RussiaTodayNewsProvider has its own implementation of the function it won’t be called because the type of newsProvider is NewsProvider. And as far as NewsProvider-extension has this method it will be used.

If you initially define a variable with specific type instead of the protocol the specific implementation will be used instead of the default one.

var newsProvider: RussiaTodayNewsProvider

newsProvider = RussiaTodayNewsProvider()

let filteredNews = newsProvider.applyFilter(filter: filter)

// RussiaTodayNewsProvider.applyFilter() implementation is used

More examples on that can be found here and here. And here is a deeper (but still quite short) explanation of the reasons by Ole Begemann.

Changes in function signature.

Imagine you have a protocol extension with the default functionality and you have some data types which have their own implementation of this functionality.

protocol NewsProvider {

func fetchNews() -> [News]

func applyFilter(filter: Filter)

}

extension NewsProvider {

func applyFilter(filter: Filter) {

// default implementation

}

}

struct RussiaTodayNewsProvider: NewsProvider {

func applyFilter(filter: Filter) {

// specific implementation... cause you know...

// these official Russian news agencies require some extra filtering

}

}

The first obstacle which might come to your mind is that you are not able to use the default implementation inside the overridden one. In case of filtering it could make sense if we want to apply some additional processing over the default implementation. So if that’s the case and we don’t want to duplicate code we need to redesign something here. But let’s leave it as it is for now.

At some point you change something regarding this applyFilter()-function in the protocol or the extension (rename the method, change its signature,…). Let’s say your smart ML-guys trained a model which can filter the fake news out of the news feed, and we might want to test it on some news aggregators:

extension NewsProvider {

func applyFilter(filter: Filter, removeFakeNews: Bool = false) {

// default implementation

}

}

Of course, the compiler makes sure that the protocol and the extension are aligned in it (in case we forgot to change it there). But if you forgot about the poor RussiaTodayNewsProvider with its unique implementation, you cannot expect any help. The compiler will just treat the old (unchanged) implementation there as a separate method (which won’t be called at all anymore).

var newsProvider: NewsProvider

newsProvider.applyFilter(filter: Filter, removeFakeNews: true)

When in the view model you will call filtering for RussiaTodayNewsProvider the default implementation will be invoked, not the specific one. Everything will work, but the result will be not the one you would expect.

Composition over inheritance… or is it?

It’s quite trendy in all the software development to talk about composition over inheritance (let me omit it here).

It’s quite trendy in Swift community to consider extensions as a good example of this principle. With the extension, we can share code and apply additional functionality without resorting to subclassing. So extensions help you to avoid such evil as subclassing. That’s true indeed (if you DO consider subclassing an “evil”) and that was one of the selling points in that famous Dave Abrahams’ talk. Extensions bring you an ability to reuse functionality of another entity without subclassing it. Moreover, you can do it with value types (which cannot be “subclassed” by definition).

The thing is that protocol extensions are not closer to composition than inheritance. Extensions do alleviate some inheritance-related pains: the connection between the data type and the extension is a bit looser, you don’t have big chains of inheritance, you don’t inherit any state from a protocol, you can conform to several extended protocols (simulating “multiple inheritance”).

Still protocol extension to me look closer to inheritance than to composition. Consider:

- you implicitly add some functionality to your data type (just one conformance/inheritance line of code)

- the connection between your data type and the extension still quite tight (compile-time connection, no real-time flexibility)

- the functionality of your data type is spread across several objects (base implementation, data-type extensions, protocol extensions), so it’s hard to grasp the full picture of an object

- you might rely on the extended functionality in the basic implementation, so if something changes there you cannot guarantee your code keeps on working as intended.

Doesn’t it remind good old inheritance?

Another complaint people have to inheritance is testability. When you test a subclass you cannot decouple it from all its parent classes, so you have to test all the hierarchy altogether. Let’s take a look at what we have in case of the protocol extensions.

Testability

If you like your code to be covered with tests, protocol extensions will give you some hard time. As we mentioned earlier we have a compile-time coupling between the extended functionality and the base implementation, no real-time dynamism. It’s hard to separate these two pieces and test them separately.

Let’s get back to our News app at the point when we moved applyFilter() function to the extension removing it from the protocol (so we have an extension with additional functionality):

protocol NewsProvider { ... }

extension NewsProvider {

func applyFilter(filter: Filter) {

// implementation

}

}

class NewsFeedViewModel {

var newsProvider: NewsProvider

// ...

func filterNews() {

newsProvider.applyFilter(filter: filter)

//...

}

}

Here we cannot test the view model independently from the NewsProvider-extension. We want to test the logic inside filterNews() method. We can mock the newsProvider, but because of the static nature of the additional functionality in the protocol extension (static method dispatch), there is no way to override applyFilter() method. And as it’s impossible to mock it, you cannot test if the view model calls it in a proper time. So you either skip to test it, or to test the filtering itself together with filterNews() method.

Testing the functionality of the extension itself is possible. But in order to do that you need to create a dummy class, make it conform to the protocol, make some dummy implementation of all the protocol’s functions not implemented in the extension. After that, you will be testing this dummy class.

class DummyProvider: NewsProvider {

// here you need to implement all the protocol methods

}

let sut: NewsProvider = DummyProvider()

let result = sut.applyFilter(filter: filter)

XCTAssertEqual(expectedResult, result)

In the end, you do test what you want to test, but it’s not so convenient.

Some alternative thinking

Sometimes protocol extensions as a feature remind me of a singleton. This pattern is also very convenient to use, it makes the functionality much more accessible and saves you a lot of extra lines of code. But most of us know that it comes at a high price.

Here are some principles which help me not overuse protocol extensions:

-

Start with a plain composition and move to protocol extensions only when you see some clear benefits in it. Protocol extensions are fancier, more interesting to write, even a bit less code. But does it really overweight all the drawbacks I mentioned before?

-

Don’t use protocol extensions just in sake of following some abstract concepts (protocol-oriented approach, to be “Swifty”, composition over inheritance). Consider readability, explicitness and self-explanatory as more important features of your code. In a lot of cases when you use protocol extensions you decrease these qualities.

-

If you feel like you need some optional methods in your protocol, consider splitting this protocol into parts. Seems like you already have at least two groups of functions (required and optional) in one protocol. Follow the Interface segregation principle.

-

Try to avoid changing default implementation into additional functionality in your protocol extensions. In case if you have some default implementation which nobody overrides, instead of removing the function declaration from the protocol consider redesign this functionality into a separate entity. Switch to a plain composition.

-

Don’t mix different protocol flavours in one. Keep your interfaces, compile-time constraints, and traits in separate objects. A lot of problems started when different functions are mixed in one object (protocol). If you mix dynamic interfaces with compile-time constraints or default implementation with the additional functionality, you are likely to be in trouble. If you still want to use all the powers of protocol extensions learn to distinguish them and separate. You can even consider using different naming conventions: “NewsProviderInterface”, “FilteringTrait”, and so on.

Conclusion

I think as always it’s all about the trade-offs.

Extensions are very powerful language concept which can help you to write more generic and reusable code. That’s a benefit.

Extensions bring additional complexity to our code. Protocol extensions bring even more complexity because of their different flavours/faces. That’s a drawback.

Then it’s up to you to set the priorities. Just remember that usually there are several solutions/approaches/patterns that you can use for any task.

… And please don’t be afraid that your code becomes less “Swifty” or less “protocol-oriented”. It doesn’t.