Usually developers get to know CADisplayLink as an advanced timer for “creating smooth frame-by-frame animation”. And that’s one of it’s application, but not the only one. Let’s take a look at the class, it’s capabilities and some general approaches to use it.

In the documentation you will find the following description:

A timer object that allows your application to synchronize its drawing to the refresh rate of the display.

It’s quite a small straightforward class with a limited functionality. Let’s see what we can do with it.

Like commonly used NSTimer or DispatchSourceTimer you customise the object, you start it and then according to its setup the timer periodically triggers some callback.

displaylink = CADisplayLink(target: self, selector: #selector(linkTriggered))

displaylink.add(to: .main, forMode: .default)

@objc func linkTriggered(displaylink: CADisplayLink) {

print("\(displaylink.timestamp)")

}

Here we create the link (CADisplayLink) without any extra adjustments and add it too the main RunLoop. In practice you can attach the link to any run loop in any thread (don’t forget that all the manually created threads and GCD-operated background threads don’t have a running run loop by default). In case of working with UI it has much more sense to use the main run loop.

The main feature of CADisplayLink is that it’s synchronised with the display refresh rate. It’s even more as an observer than the timer itself, because the triggering event is initiated by an event and not directly by a time tick. The triggering event is refreshing the frame (aka v-sync) so by default CADisplayLink’s callback is being called right after another frame is rendered. If you have 60fps refresh rate on your device the callback will be triggered not just every 16.6ms (1/60 of a second is approximately 16.6ms), but right after the frame update. So you can be sure that you have all the 16ms to render the next frame. (In case of NSTimer or DispatchSourceTimer the correlation with the frame update is quite random, depending on the time when the timer was started, so it can be 16ms in the best case, or something 3ms).

Ok, callbacks for every frame.. what else can we do with CADisplayLink? Not so much, but there are something more.

Frame juggling

There are different ways in iOS to manipulate the UI. You can work with UIKit classes, placing the views and doing UIView-based animations. You can work with CoreAnimation, handling CALayers and performing CAAnimation. You can get one level lower and use CoreGraphics with it’s contexts, shapes and paths. If it’s still not enough of a control or you need more fine grained adjustments you can work directly with GPU using OpenGL or Metal. CADisplayLink may be very helpful on the two lowest levels: CoreGraphics and OpenGL/Metal, when you can take responsibility for drawing each particular frame.

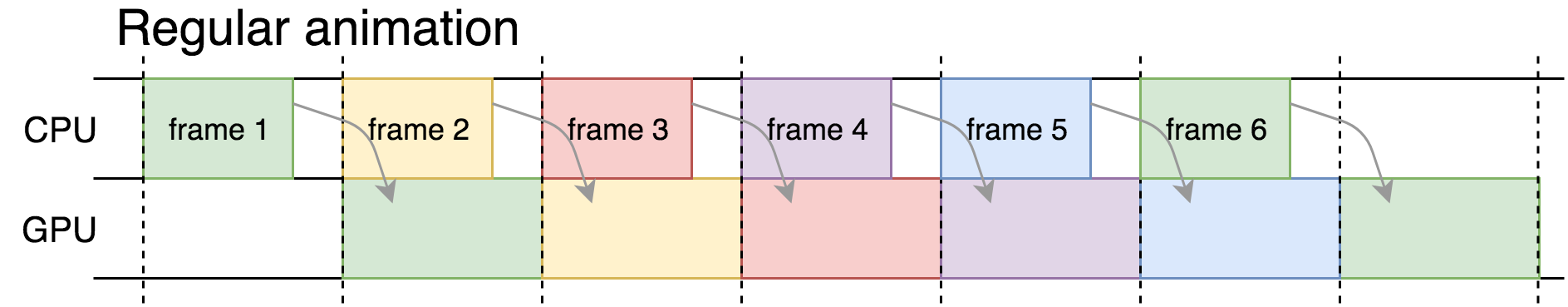

All that you see on the device’s screen is a cooperative work of CPU and GPU. CPU calculates frames’ content, GPU is responsible for displaying it on screen. CPU and GPU work asynchronously, so when GPU is displaying the 1st frame, CPU is already calculating the 2nd one. Until CPU is done with the calculations GPU has nothing new to display, so it keeps the previous frame on screen.

On this picture you can see how frames switch each other. The vertical dotted lines separating each of these boxes is the display refresh. This is the point in time where one frame on the display is swapped out with the next one to be shown. In the first row we will show rendering of the frame (made by CPU), below in the second row we consider displaying the frame on screen (made by GPU).

Regular animation

Above is a scheme of a normal animation mode (let’s call it “Regular”). Every frame is being rendered in less than 1 frame time so it’s appropriately displayed in the next frame slot. Hence in 6-frame time frame we have 6 displayed frames - perfectly smooth animation with a real speed.

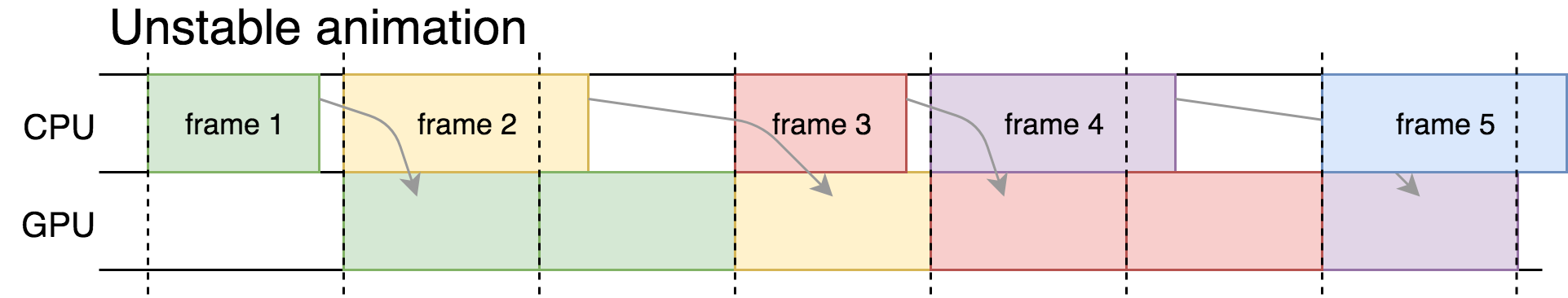

Unstable calculation

Here is the situation where in some cases 1 frame time slot is enough for us to calculate the frame content, but in other cases - that’s not enough. When the frame is not rendered in time GPU keeps the previous one on screen and changes it only in the next frame time. As a result some frames are on screen a twice longer than they supposed to be so the animation looks jerky because the speed of switching frames is unstable Over all speed of the piece is slower than expected (the duration of the clip is longer) - you can see that in our case: we have just 4 frames in a 6-frame time.

Heavy calculation

This example depicts the situation where our calculation always takes more time than one frame. As a result every frame takes twice more time to display than intended and in 6-frame time we have only 3 frames displayed. Animation became twice slower than it should have been.

I created a sample project to show the difference between these types of frame calculation (with some artificial overhead): sample project on GitHub

Time-related properties

Basic time-related properties of CADisplayLink are timestamp, targetTimestamp and duration.

- timestamp is the time of the last displayed frame, the starting point of your calculation.

- targetTimestamp is the time of the next frame to trigger the link. And

- duration is the time interval between two frames - it’s constant for the link.

duration = targetTimestamp - timestamp

There is another important property: preferredFramesPerSecond. By default it’s 0 and your link is triggered with the maximum possible rate, which means if you have a device with 60fps refresh rate, the frame rate of the link will be 60fps as well. In some cases you might want to make your updates more sparse (30fps, 10fps) - for instance, if you know that 16ms might be not enough for your calculations. So you just change preferredFramesPerSecond and your link gets triggered less frequently.

The property is called “preferred” because there are several predefined values of the actual frame rate which are all factors of maximumFramesPerSecond (the property of UIScreen). If maximumFramesPerSecond for your device is 60fps that means you can decrease the link’s frame rate to 30fps (so the link will be called every 2nd frame), to 20fps (every 3rd frame), to 15fps (every 4th frame) and so on. It’s called “preferred” because you tell the system what rate would you like, and the system tries to satisfy you within its capabilities. If you set preferredFramesPerSecond to, let’s say, 27fps the system will round it to the closest valid value which is 30fps which will be the frame rate of your link.

Coming back to our examples, both “unstable calculation” and “heavy calculation” cases require decreasing the frame rate. That means you aware that your code cannot calculate 60 frames per second, so you calculate less of them (30 for instance) and keep your animation smooth. The frame change scheme will look like the “heavy calculation” one - with 3 frames calculated for 6 frame time - with the crucial difference that in this case each frame supposed to be shown twice longer, so you have real animation speed.

Some non-obvious things to keep in mind when dealing with preferredFramesPerSecond:

- If you set it to the value less then maximum for your device don’t expect

durationto change. It indicates the duration of one frame, not the time difference between your callback calls. So if you want to calculate the time difference from the previous call usedisplaylink.targetTimestamp - displaylink.timestamp - If you want to set it to 120 you might need to set

CADisableMinimumFrameDurationkey in yourinfo.plistfile (it was a temporary solution from Apple for iPad Pro, they promised that at some point everything would work by default)

Invalidation

For controlling the lifecycle of CADisplayLink you have two options: temporary pause the link (stop it from firing your callback) and invalidate it completely.

displaylink.isPaused = true

displaylink.invalidate()

It’s important not to forget about invalidating the link when you don’t need it anymore. Even if you don’t do anything in the callback firing it 60 times per second is still a load on CPU, which eventually will affect the battery life of the device.

Control over the long running calculation

One more useful trick when using CADisplayLink is keeping an eye on the current time. You might want to change the logic depending on you current progress or even cancel the calculation of some frame if the calculation is too heavy at the moment.

@objc func linkTriggered(displaylink: CADisplayLink) {

for pixel in pixelMatrix {

// some calculation here

if (CACurrentMediaTime() >= displayLink.targetTimestamp) {

// no more time

break

}

}

setNeedsDisplay()

}

How would one use CADisplayLink

Talking about the general applications of the CADisplayLink let’s get back to the original description. If I rephrase it I can say that it’s a way to connect your model to your UI the way, that is optimal for the specific device. Let’s take a look at these three entities.

The Device. Nowadays majority of iOS devices work on 60Hz, but iPhone 4 with it’s 30Hz display is not such a distant past and iPad Pro with 120Hz was released more than a year ago. So you have to admit that maximum fps of the hardware is just a parameter - not a constant and your app should be ready to work with all the possible values of this variable. CADisplayLink perfectly incapsulates this parameter (if you don’t set preferredFramesPerSecond property) so you forget about the hardware and work only with timestamps and durations.

The Model. CADisplayLink makes sense when dealing with complicated models. It can be an object graph of the game or a video which you want to process applying some filters and modifications or some other complicated state which rapidly changes. CADisplayLink can also help you out if you have some sort of data provider which transmit some date with an extremely high frequency - 100, 200, 500 times per second and you need to decrease it to the necessary minimum of 30/60 fps in the UI. It’s quite a common situation in the world of medical or physical measurements which deal with electrical impulses (don’t underestimate their need in iOS apps ;-)).

The UI. So you have to present some changing state to the user. But you have to be care using CADisplayLink otherwise it can bring you more harm than the benefits. On one hand you shouldn’t put it everywhere, because in the majority of cases you don’t need an update so precisely coupled to your frame rate. Out of the rest cases the big set can be easily covered by easier approaches: UIView-animations, CAAnimations, UIKitDynamics. If your CADisplayLink is being called several dozens times per second for nothing, well.. you just carelessly use user’s CPU and battery resources. On another hand when you need to immediately process changes of some state, when the delay in milliseconds is significant, CADisplayLink is your way to go. But you still don’t want to trigger your calculations more often than necessary. You might not need 120fps or even 60fps for your task so don’t create and overhead (remember preferredFramesPerSecond property).

Useful links:

https://developer.apple.com/documentation/quartzcore/cadisplaylink

https://developer.apple.com/videos/play/wwdc2014/236

https://developer.apple.com/documentation/metal/advanced_command_setup/cpu_and_gpu_synchronization

https://developer.apple.com/library/archive/technotes/tn2460/_index.html (CADisableMinimumFrameDuration key)

https://github.com/DmIvanov/Animations (my sample project)